Click here to view Pt. 1 of The Spring of August

Last month, we looked at the road August Wilson took to becoming a playwright. This month, we examine some of his works, and look at the praise and criticism his works and actions have garnered.

THE ORIGIN: "Jitney" is one of Wilson's first notable

plays.

The success that "Jitney" would have in its run in Minnesota would serve as a precursor for the acclaim Wilson would receive for his follow up. "Ma Rainey's Black Bottom" (the only play in Wilson's ten-play cycle that is not set Pittsburgh, but in Chicago) was accepted by Connecticut's National Playwrights Conference of the Eugene O' Neill Theatre Center, opening in April of 1984 at the Yale Repertory Theatre in New Haven. It was with this production that a long creative partnership with Lloyd Richards (the Eugene O'Neill Center's Director and the Yale Dean of Drama) began.

Fences, a quick successor, opened in 1987 on Broadway and went on to win four Tonys, the New York Drama Critics Award, and the Pulitzer Prize. Wilson's next production, "Joe Turner's Come and Gone" opened on Broadway in March of 1988, making August Wilson a black playwright with two plays running simultaneously on the Great White Way.

A PERFECT COMBINATION: The inaugural run of "Ma

Rainey's Black Bottom" marked the beginning of

Wilson's long creative partnership with director Lloyd

Richards.

The themes these plays present are as notable as the reception they received. "Ma Rainey's Black Bottom" focuses on a 1927 recording session for a legendary black blues singer. The backing band, with each member representing a different facet of the black community, is ridiculed by a white producer for their playing technique. The play reaffirms, through the words of the singer herself, the idea that the blues are the black community's way of channeling and communicating our frustration. Fences, set in the 1950's, deals with Troy Maxson, a garbage man, and his struggles with his past. Troy, who never had a chance to play in the Major Leagues due to racism, is bitter towards black players who found mainstream success and forbids his son, Cory, a football star, from playing on the team, even though a recruiter from North Carolina has expressed interest in him. "Joe Turner's Come and Gone" focuses on Herald Loomis, a man who has just completed an unjust seven-year sentence of hard labor in Tennessee and arrives, rightfully bitter, at a boarding house in Pittsburgh in search of his wife and daughter.

GENERATION GAP: With keen analysis of the relationship

between black fathers and black sons, "Fences" won

over critics and fans alike.

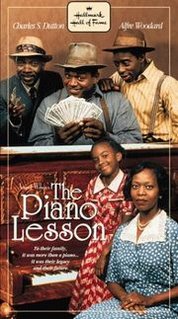

NO MIDDLE GROUND: August Wilson's "The Piano Lesson,"

thought to be his most polarizing work, won a Pulitzer

Prize and was adapted into a television movie.

Both the praise and the criticism leveled at Wilson would come to a head with his next work. "The Piano Lesson" centers around a conflict between brother and sister with regard to the family heirloom: a piano that was stolen from the family of a slaveowner after being used to purchase some of the family's ancestors into captivity; the brother wants to sell it, in order to buy the plantation on which his ancestors once worked, while his sister wants to keep it as a symbol of the family's triumph over unimaginable adversity. In addition to this struggle, the two must deal with the spirit of a deceased descendant of the aforementioned slaveowner.

IN FULL CIRCLE: "Radio Golf," which represents the

90’s in Wilson's ten-play cycle, debuted just a few

months before Wilson's death.

DARK DAYS: "King Hedley II" represents the 80's in

August Wilson's ten-year cycle.

Like his plays, Wilson's social stances became polarizing. In 1987, Paramount Pictures obtained the rights to make "Fences" into a motion picture. When Wilson learned that the studio had planned to have Barry Levinson (of "Diner" fame) helm the project, Wilson balked. In 1990, Wilson wrote an op-ed piece for the New York Times entitled "I Want A Black Director" in which he defended his position, stating that he feared that a white director would have neither the knowledge of, nor the sympathy towards, the black experience needed to properly convey the story's message. (Wilson took pains to make it clear that he disapproved of Levinson's assignment on the basis of culture, not race.) He also addressed what he saw as Hollywood's general lack of faith in black directors. (In this way, Wilson could be thought of as

a pioneer of a different vein: this type of filibuster would be enacted again in the mid-90s by director Spike Lee when Lee called for the removal of Norman Jewison ("In The Heat Of The Night") from the director's chair for "Malcolm X," eventually to direct the film himself.

Furthermore, his address at the 1996 Theatre Communication Group National Conference entitled "The Ground On Which I Stand" drew criticism for its condemnation of color blind casting in theatrical productions and its call for self-contained black theater companies. In the speech, Wilson also expressed discontentment with the belief held by many theater purists that the influx of multicultural works had lowered the quality of theater as a whole. The speech started an epistolary joust between Wilson and Robert Brustein, the Artistic director of American Repertory Theater at Harvard University, which culminated in a 1997 public debate at New York City Town Hall. (While many people lauded the diplomatic manner in which the two men conducted themselves, they also regretted that no agreement could be reached.) It is worth noting that, even though many black actors and intellectuals openly disagreed with Wilson's views, they respected the fact that, at a time when the theatrical world was struggling for attention, a black man put this artistic community back in the public eye.

IN TOUCH: August Wilson signing an autograph for one

of his many fans.

The voice of August Wilson was silenced on October 2, 2005 when the playwright lost a battle with liver cancer (Wilson had just completed his ten play cycle a few months earlier with the debut of "Radio Golf," a commentary on urban renewal and black career mobility, set in the 1990's.) 14 days after his death, Wilson became the first African-American to have a Broadway theatre named in his honor when New York's Virginia Theatre was renamed The August Wilson Theatre.

Although "The Ground On Which I Stand" caused a great deal of controversy, one of its main points needs to be reiterated: the ground on which Wilson stood was firmly in the black experience, but his plays also provided mainstream audiences universal themes with which to identify. This point is brought home in a quote concerning the character of Troy (from "Fences") from a 1999 interview with literary journal "The Paris Review":

SILENT, BUT STRONG: Many people were disarmed by the

fact that, despite having a burly physique, August

Wilson was soft-spoken in demeanor.

Here in America whites have a particular view of blacks. I think my plays offer them a different way to look at black Americans. For instance, in Fences they see a garbage man, a person they don't really look at, although they see a garbage man every day. By looking at Troy's life, white people find out that the content of this black garbage man's life is affected by the same things--love, honor, beauty, betrayal, duty. Recognizing that these things are as much part of his life as theirs can affect how they think about and deal with black people in their lives.

To view more writings, articles and perspectives from the cultural analyst known as Mr. Byron Lee please visit his official blog @ http://www.weallbe.blogspot.com

No comments:

Post a Comment