Illinois Teen Employment At New Low

Decline Puts Jobless Youths At Risk Of Falling Further Behind Economically For Years To Come,

Says New Report

By Julie Wernau

Chicago Tribune staff reporter

January 26, 2010

Eighteen-year-old Gabrielle Banks braids her friends' hair on the West Side for car fare money. The Community Christian Alternative Academy student has been looking for a job since last summer, when she worked at her high school as an "ambassador" for health and fitness, back when the program was funded.

"I don't just think I want a job. I think I need a job," she said, "My mom, she's the only income we get, and there's four of us. I could help out with things like groceries, cleaning supplies, toothpaste, stuff like that."

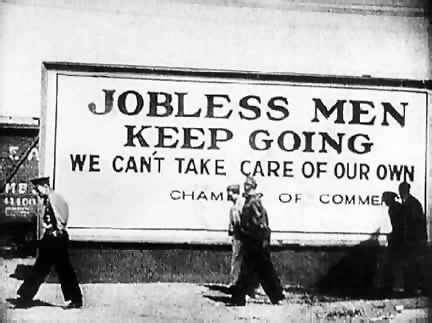

Banks is part of an unprecedented number of unemployed teens in the state, a fact state and local leaders say puts them at risk of falling further behind economically for years to come.

A report by the Center for Labor Market Studies at Northeastern University, commissioned by the Alternative Schools Network and set to be announced Tuesday in Chicago at a Youth Hearing on Education, Jobs and Justice, says the employment rate for Illinois teens in 2009 was more than 20 percentage points below 2000, marking a new low for the state.

Experts say youths who spend substantial time away from school and work run a greater risk of being jobless, poor or incarcerated by their early and mid-20s. The city's alternative schools, the Chicago Urban League and other advocates are calling for the allocation of $1.5 billion in federal stimulus money for youth-employment and re-enrollment programs nationally.

They say that money would trickle down to the state level to assist more than 25,000 youths in Illinois, including 9,000 in Chicago who are jobless.

With 72,800 unemployed 16- to 19-year-olds in the state through November and another 110,000 unemployed 20- to 24-year-olds, even that level of funding would be a drop in the bucket.

"If kids don't have jobs, they don't have a chance to learn what it is to have a job," said Jack Wuest, executive director of the Alternative Schools Network in Chicago.

In the 1980s, Chicago employed 35,000 youths each summer using federal money. The money dried up by 2000. At the time, teens in Illinois were nearly 1.4 times as likely to be working as those who were 55 and older, but within a year the rates shifted in the other direction.

Joe McLaughlin, senior research associate for the Northeastern study, calls it "the lost decade." The teens who were 16 to 19 in 2003-2007 now are in their 20s and staring down unprecedented levels of unemployment, he said.

"Teen and young adult employment is very past-dependent," he said. "The more you work today, the more you will work in the future. The intensity of your work ethic influences the intensity of your work ethic in the future."

Last summer, for the first time in nine years, $1.2 billion was allocated across the country for youth employment programs. Anne Sheahan, director of public information for the Chicago Department of Family and Support Service, said that translated to $17.3 million and jobs for about 7,800 youths in Chicago. That, combined with the city's Youth Ready Chicago program, a public-private collaboration, employed about 20,000 youths in the city, including the job Banks had. But, Sheahan said, 75,000 youths applied. A similar bill has been proposed this year, and its fate would directly translate to the number of jobs Youth Ready Chicago can provide.

Employment statistics are particularly abysmal among low-income youths and young African-American males in the city. In Chicago, only 15 percent of black teens held any type of job in 2008 versus 30 percent of Latinos and nearly 33 percent of whites. Just 12 percent of low-income students (family income of less than $20,000) were working in 2008 versus 23 percent of those in families with incomes of $40,000 to $60,000.

"Those trends for 16- to 19-year-olds, 20- to 24-year-olds, overlaid with other statistics — violence, crime, incarceration, literacy rates, all of the really hardcore statistical evidence — you just come away with a very disturbing trend," said Herman Brewer, acting president and CEO of the Chicago Urban League.

Since summer, Ashley Cartagena, 16, has been hoping to juggle homework with an after-school job. The Campos High School student would like to make a few dollars to help out her family. She'd like to work retail so that she can get a discount on her school clothes.

She hasn't heard back from any of the retail stores where she has applied.

"I just keep applying because sooner or later someone is going to have to call or tell me something," she said.

Cartagena has been keeping busy at after-school programs and worked cleaning and maintenance jobs through her school over the summer.

Monday, Banks walked five blocks to and from the train, through a rough neighborhood where drug dealing could be seen in plain view, to get to school and back.

She is applying to colleges in Georgia, hoping to get out of the city.

David Thigpen, vice president for research and policy at the Chicago Urban League, said if employment numbers don't improve, more companies will choose not to come to Chicago.

"We have to think about ... the fact that we are competing with other big cities for talent," Thigpen said.

jwernau@tribune.com

"I don't just think I want a job. I think I need a job," she said, "My mom, she's the only income we get, and there's four of us. I could help out with things like groceries, cleaning supplies, toothpaste, stuff like that."

Banks is part of an unprecedented number of unemployed teens in the state, a fact state and local leaders say puts them at risk of falling further behind economically for years to come.

A report by the Center for Labor Market Studies at Northeastern University, commissioned by the Alternative Schools Network and set to be announced Tuesday in Chicago at a Youth Hearing on Education, Jobs and Justice, says the employment rate for Illinois teens in 2009 was more than 20 percentage points below 2000, marking a new low for the state.

Experts say youths who spend substantial time away from school and work run a greater risk of being jobless, poor or incarcerated by their early and mid-20s. The city's alternative schools, the Chicago Urban League and other advocates are calling for the allocation of $1.5 billion in federal stimulus money for youth-employment and re-enrollment programs nationally.

They say that money would trickle down to the state level to assist more than 25,000 youths in Illinois, including 9,000 in Chicago who are jobless.

With 72,800 unemployed 16- to 19-year-olds in the state through November and another 110,000 unemployed 20- to 24-year-olds, even that level of funding would be a drop in the bucket.

"If kids don't have jobs, they don't have a chance to learn what it is to have a job," said Jack Wuest, executive director of the Alternative Schools Network in Chicago.

In the 1980s, Chicago employed 35,000 youths each summer using federal money. The money dried up by 2000. At the time, teens in Illinois were nearly 1.4 times as likely to be working as those who were 55 and older, but within a year the rates shifted in the other direction.

Joe McLaughlin, senior research associate for the Northeastern study, calls it "the lost decade." The teens who were 16 to 19 in 2003-2007 now are in their 20s and staring down unprecedented levels of unemployment, he said.

"Teen and young adult employment is very past-dependent," he said. "The more you work today, the more you will work in the future. The intensity of your work ethic influences the intensity of your work ethic in the future."

Last summer, for the first time in nine years, $1.2 billion was allocated across the country for youth employment programs. Anne Sheahan, director of public information for the Chicago Department of Family and Support Service, said that translated to $17.3 million and jobs for about 7,800 youths in Chicago. That, combined with the city's Youth Ready Chicago program, a public-private collaboration, employed about 20,000 youths in the city, including the job Banks had. But, Sheahan said, 75,000 youths applied. A similar bill has been proposed this year, and its fate would directly translate to the number of jobs Youth Ready Chicago can provide.

Employment statistics are particularly abysmal among low-income youths and young African-American males in the city. In Chicago, only 15 percent of black teens held any type of job in 2008 versus 30 percent of Latinos and nearly 33 percent of whites. Just 12 percent of low-income students (family income of less than $20,000) were working in 2008 versus 23 percent of those in families with incomes of $40,000 to $60,000.

"Those trends for 16- to 19-year-olds, 20- to 24-year-olds, overlaid with other statistics — violence, crime, incarceration, literacy rates, all of the really hardcore statistical evidence — you just come away with a very disturbing trend," said Herman Brewer, acting president and CEO of the Chicago Urban League.

Since summer, Ashley Cartagena, 16, has been hoping to juggle homework with an after-school job. The Campos High School student would like to make a few dollars to help out her family. She'd like to work retail so that she can get a discount on her school clothes.

She hasn't heard back from any of the retail stores where she has applied.

"I just keep applying because sooner or later someone is going to have to call or tell me something," she said.

Cartagena has been keeping busy at after-school programs and worked cleaning and maintenance jobs through her school over the summer.

Monday, Banks walked five blocks to and from the train, through a rough neighborhood where drug dealing could be seen in plain view, to get to school and back.

She is applying to colleges in Georgia, hoping to get out of the city.

David Thigpen, vice president for research and policy at the Chicago Urban League, said if employment numbers don't improve, more companies will choose not to come to Chicago.

"We have to think about ... the fact that we are competing with other big cities for talent," Thigpen said.

jwernau@tribune.com

Copyright © 2010, Chicago Tribune

No comments:

Post a Comment