The Intergenerational Connection: Civil Rights Veteran John Steele & R2C2H2 Tha Artivist

John Steele: Where’s Our Mississippi?

2/3/2009

[Available as a printable PDF pamphlet]

By John Steele

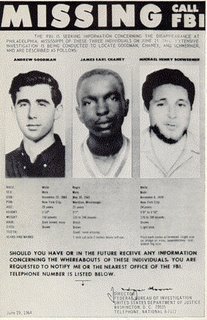

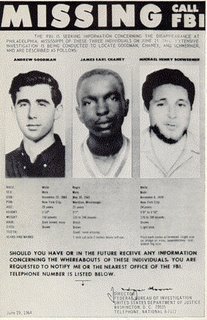

In the summer of 1964, three civil rights workers were murdered in Mississippi. They are known to the world as Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner. But back then, in the days before they died, I knew them as Andy, JE, and Mickey.

I want to share with you my memories of the time we drove south together to join the Mississippi Freedom Summer project. I want to tell a bit of the story of that summer, and tell it for a purpose. I believe it has implications for today.

Driving South

Mickey was driving as we pulled out of Oxford, Ohio in his station wagon, windows down, through the lush green of early summer. The four of us were volunteers. We were excited. And we felt some fear. We were part of a project to fight white supremacy in Mississippi, where the most basic democratic rights were denied to African American people. We were going to throw ourselves into the front lines of a cause that called itself, simply, the Movement.

I had dropped out of college, and didn’t know what I’d do in the long run. But this battle — black people mounting an intense struggle against an entrenched and clearly evil system – was completely, utterly galvanizing for me. I got my father’s signature (necessary because I was under 21), but we didn’t inform my mother until I was already gone. She was very upset, angry and afraid, when she found out. And of course, she had reason to be upset. Six black civil rights workers had already been killed in just the first five months of 1964, in the state of Mississippi. There had been no indictments. No charges brought against the killers.

| |

|

Mississippi was a place where African American people were killed with impunity. And often the victims were tortured before the murder, and their bodies often mutilated in horrible ways with gouging and castration. No white person had ever been convicted of killing a Black person in Mississippi. Never.

Once our car crossed on into the South, J.E. climbed all the way into the back of the station wagon, to sit by himself, because just having black and white seated side-by-side in our car was dangerous. Our mixed crew risked attention at highway restaurants for the same reason, and so we made the 16-hour trip on snack food. Not that any of us was very hungry.

J.E. was just twenty-one, rather quiet, a young black man who had made the decision to step forward in this battle. He was a native of Meridian, the small city in Mississippi we were going to. And he seemed at peace with his decision, although he certainly knew better than any of us exactly what we were facing. Me and the other volunteers knew what we believed in — there was a intense sense of moral justice that carried the Movement through everything it did — but we still had only the vaguest idea of the world we were entering and the forces in America we were going to be challenging.

I remember Andy in the car, talkative and inquisitive, questioning Mickey about what to expect. Mickey was a little older (twenty-four) and the leader of our team. With his goatee and energetic assertiveness, he seemed authoritative. But he’d only been in Mississippi six months. He and Chaney were members of CORE (the Congress of Racial Equality) one of the activist groups working together on the summer project.

Joining SNCC, Building MFDP

| |

|

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (called “snick”) had been formed by participants in the 1960 Nashville sit-ins against whites-only lunch counters. And it had dared to bring the Movement into Mississippi two years later. It emerged as one of the most radical, committed and controversial projects in a very conservative America.

In those days, the South had been in the grip of Jim Crow segregation, an American apartheid, for almost a hundred years. African American people were officially denied basic rights, and forced into separate and inferior conditions – as they were bitterly exploited. Here in many small rural farming towns of the old cotton economy, many black people were still imprisoned in a dying semi-feudal system of share-cropping and debt that left them brutally poor, uneducated, and increasingly discontent.

All over the South, African American people were taking on this segregation – led and organized by radical students (as in SNCC and CORE), or returning veterans (like NAACPs Robert Williams) or respected ministers (like the network around Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference).

I’d been aware, excited, seeing this building over several years, watching people face police dogs and fire hoses. But at first only from a distance. Now I’d thrown myself into it.

This Mississippi Freedom Summer was about breaching Jim Crow where it was strongest. Hundreds of college students, both black and white, were recruited to make a breakthrough in this most backward, racist and rural of states, to break open this closed and vicious society. It was a movement built by the young.

Our team was involved in registering people to vote. Under Jim Crow, African American people were simply not allowed to vote – which meant that the elected sheriffs were brutal racists, and the juries were all white, and the whole power structure was openly defined by white supremacy. Those black people who stepped forward to register were told they had to interpret some obscure section of the Mississippi Constitution (to supposedly prove their literacy), and naturally no matter what they said the racist gatekeepers of the system would say it wasn’t right. But more, just going to the courthouse to register meant you were targeted, in ways that everyone understood and feared.

The voter registration during the summer of 1964 was more than just a way of demanding a basic legal right – it was a means of building organization among the people: We were registering people as members of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). This was a political organization formed in parallel (and really in sharp opposition to) the regular Mississippi Democratic Party. Mississippi was a one-party state, and the all-white regular Democratic Party was a stronghold of raw, violent, official white supremacy. The new MFDP was a challenge to all that – it was open to both black and white, and it was a political party opposed to segregation and rooted among African American people (who have always been the majority of people in Mississippi). The plan was that MFDP would hold its own state convention, elect delegates to the national 1964 presidential convention of the Democratic Party, and demand seating in place of the delegates of racist regular Democratic Party (who were, quite obviously, representatives and enforcers of this hated Jim Crow system).

Pulling Into Meridian

| |

|

We drove down the one main street of Meridian into the black section of town, pulling up along some low-rise brick apartments. Local people risked their lives to open their homes to us. The couple I stayed with was young. Another volunteer and I stayed in their small second bedroom – the “kids room” in their plans. He was a carpenter’s assistant and she worked cleaning the houses of white people. I don’t remember their names.

As we pulled up to connect with our contacts, we were a true sensation. “White civil rights workers from the North!” Black teenagers crowded around us, excited, laughing, asking questions. This movement represented the only hope they had, and they knew it.

For the white volunteers, the fearlessness of the black people of the South had been our inspiration. And yet, at the same time, the fact that white people were involved was a source of great interest to those living under Jim Crow – it was a witness that people cared what they were going through. It brought a sense of potential allies in the wider world outside Mississippi, and of the possibility that “black and white together” might create a different way of life.

Even before leaving Ohio, we’d known we would be arriving in Meridian in the middle of a crisis. A black church had just been burned to the ground, and several of its elders beaten. It was in Philadelphia, a notorious redneck town thirty miles away.

Mickey and J.E. had already been talking to people there about using their church as an organizing center for Freedom Summer. This burning was the Klan’s response. And so, as soon as we arrived, Mickey and J.E. immediately decided to take the station wagon to Philadelphia the next day. They asked Andy to come with them. The three left that Sunday morning – planning to return later that afternoon.

The rest of us, both volunteers and local teenagers, gathered in the Movement’s community center — a second-floor loft, with desks, phones and a reading library. We hung out, just getting to know each other, while we waited for the three to return.

Time passed. They were late. And we began to get nervous.

SNCC had security procedures: if anyone was delayed they were supposed to call in — though finding a pay phone on those rural roads was not easy.

So now we did what we’d been trained to do. First we notified our project’s headquarters in the state capital that the three were late. Then we called every hospital and jail in the surrounding area. The reply was always the same: “No, we haven’t seen them.”

| |

|

We had been in Mississippi less than 24 hours and three of us were missing.

The afternoon turned into evening and still no word. We went out for a bite to eat. No one wanted to voice our fears. As the evening grew late two cars and a pickup truck, driven by white men, circled our block several times. It was a threat, and we telephoned in their descriptions and license numbers. Some of us spent that night at the center, sleeping on the floor.

On Tuesday Mickey’s burned-out station wagon was found.

Searching Every Swamp

We didn’t talk about it, but we all knew in our hearts that they had probably been killed.

Newspapers in Mississippi…. To read them was to get an understanding of the social structure they served. When our three organizers disappeared, the local papers responded almost unanimously with the speculation that these “outside troublemakers” had probably staged a hoax, and that the three were most likely “up in New York somewhere, laughing at all fuss.”

And it was not just the press, of course. Mississippi as a whole was a very closed society. The whole power structure of the state was highly interlocking (much more than we knew at the time) — from the governor’s mansion down through the businessmen and lawyers in the White Citizens Councils, through local police sheriffs, and Klansmen circling our office that night — all mobilized for the defense of white supremacy (in the name of “states rights” against “outside intervention.”)

We didn’t know it then, but the state government’s spies had gathered names and license plates on all of us that summer — forwarding them to the Ku Klux Klan. State officials visited county sheriffs, briefing them on which laws to use in arresting civil rights workers.

But suddenly with the disappearance of our three comrades, the whole world was watching. Reporters poured into the state. There was a tremendous pressure building to find the three missing civil rights workers — and to find out what had happened to them.

President Lyndon Johnson (LBJ) ordered the FBI into a highly visible role in the search and investigation Meanwhile, behind the scenes, the same FBI (directed by Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy) was spying on the Civil Rights activists and leaders, and its operatives within the Klan were repeatedly involved in brutal attacks on the Movement.

| |

|

The search for Mickey, J.E. and Andy was massive. Even sailors from a local naval base were brought in to wade through swamps and drag the rivers. But their bodies were not found. What the searchers did discover were the bodies of at least two black men in those rivers and swamps.

Welcome To Mississippi.

Mississippi’s governor mobilized the state police to watch, but not to help. They shouted racist jokes as long lines of searchers waded through swampy waters.

Our Work

“We are black and white together, we shall not be moved”

While all this was going on, we pressed ahead with our work.

I was part of a small team that went into the little towns and farms of Lauderdale County. Black and white teams, knocking on doors, we talked to people about the struggle, and invited them to join us. We had big mass meetings every week, gathering everyone possible from the area, to lay plans and to sing freedom songs together.

It is hard to capture the atmosphere of hatred and threat that surrounded us – and that had defined the lives of African American people here for since the creation of the plantations. We were portrayed as despicable, dirty, unwashed “n*gger lovers” who had come to Mississippi to destroy a beloved way of life, like new invaders from the North, under the direction of “godless communists” – and often as twisted degenerates determined to expose “white Christian Southern womanhood” to the dangers of “black rapists” and race-mixing.

In one situation, I went with a group of us to order food at a restaurant in the bus station. It had been forbidden for black and white to sit together and eat. The old and strictly enforced rules forbade black people from using the same washrooms and lunch counters as white people. And so we were just going to challenge all that. A group of white teenagers pulled into the restaurant booth next to us, and the hostility escalated – first taunts, then spitting, then threats. And everyone understood, of course, that their actions would be completely backed by the local sheriffs and the Klan (who were often the same people).

In another situation, I was walking with one of my black comrades and a car started tailing us – driving very slowly behind us in an obviously threatening way. Just the two of us, walking together, was seen as a challenge to everything about this society. We tried to act like we were ignoring him. But then as we started crossing an intersection, he accelerated rapidly and tried to run us down.

Multiply these incidents a hundred times, and you get a sense of what was going on all across the state. Through it all, awareness of the missing three was always with us. It was a grief that didn’t dare declare itself, and an anxiety that became part of the uncertain threatening background. But honestly, the joy and feeling of fellowship among people in struggle, the excitement of important (and yes, dangerous) work, and the wonderment of discovery too (I for one had known nothing at all of black people and their culture first-hand) – these were the uppermost feelings.

One focal point of all this was the Democratic presidential convention later that summer of 1964 in Atlantic City. After all the risks taken by the people, a delegation of MFDP went to demand a seat at the table. We intended to trigger the public support by the central national power structure – as a way of weakening and isolating the local defenders of Jim Crow in Mississippi and the rest of the Deep South.

And then came a crucial moment of political education – for us in SNCC and CORE, for the African American people, and for everyone watching the Movement. LBJ’s forces, in control of the convention refused to countenance any breaking of ties with the Mississippi regulars. The white racist power structure of the South was a key pillar to how the whole U.S. was ruled – it was key to the functioning of the Democratic Party and had been from the beginning. And acceptance of this most naked white supremacy was normal to how politics – at all levels — worked in America.

After much negotiation by liberals in the party, the MFDP was offered a couple of honorary nonvoting seats. The MFDP refused the insulting offer.

A Very Infuriating-But-Enlightening Defeat.

It may be hard now to reconstruct the sincere hopes and illusions we had for reforms of this system. You have to imagine away many of today’s layers of automatic knowingness and cynicism. We had really thought the Democratic Party would respond in good faith to the clarity of the moral and political demands upon it. Its refusal was one of those experiences that move the thinking of whole swaths of people, and plant the seeds for new conclusions. It began the process of lifting a few veils, tearing at our illusions, and beginning to reveal the ground on which we actually stood.

The Last Hours Of Goodman, Chaney And Schwerner

Finally, in early August, six long weeks after their disappearance, someone on the inside of the Klan, tempted by reward money, told the secret. Our brothers were buried deep in an earthen dam.

Finally, in early August, six long weeks after their disappearance, someone on the inside of the Klan, tempted by reward money, told the secret. Our brothers were buried deep in an earthen dam.

We know now what happened that night when our comrades died. They had gone to talk to supporters in Philadelphia, and were arrested as they left. While they were held in the Neshoba County Jail, the Sheriff, his Deputy and Edgar Ray “Preacher” Killen – the three of them all members of the Klan – brought in Klansmen from the surrounding area to prepare an ambush.

Late that night, Mickey, J.E. and Andy were released and escorted to the Philadelphia town line. And then, a few miles later, their station wagon was stopped again — and they were taken away at gunpoint. Schwerner and Goodman were shot point-blank. Chaney broke free and ran. He was shot, dragged back. As the black man in the crew, he was singled out for special punishment. He was beaten mercilessly, shot again, and his body was mutilated. His killer reportedly said to the other Klansmen, “You didn’t leave me anything but a n*gger, but at least I killed me a n*gger.”

The three bodies were driven to a nearby dam construction and covered over by bulldozer.

The Klan wanted to break the organized core of the movement. But they failed. As the bodies of the three were lifted out of that dam, the whole watching world could see the ugliness and the murderous structure of white supremacy in America. These killings incited widespread outrage and anger, brought people forward into active struggle or support.

Mississippi CORE leader Dave Dennis addressed us and our whole generation as he delivered the eulogy for James Chaney: “Your work is just beginning. If you go back home and sit down and take what these white men in Mississippi are doing to us. …if you take it and don’t do something about it. …then God damn your souls.“

And Now?

I have not written about the summer of ‘64 before, and I don’t do it now in order to memorialize a righteous struggle of yesterday. My purpose and thoughts are much more focused on today – and tomorrow.

I have not written about the summer of ‘64 before, and I don’t do it now in order to memorialize a righteous struggle of yesterday. My purpose and thoughts are much more focused on today – and tomorrow.

What swept me into the civil rights struggle was in large part the utter moral clarity of what was involved: the clear evil of institutionalized white supremacy, and the courage and nobility represented by the movement which was going directly up against it.

Is such clarity possible today?

Well….We have a war in Iraq of unrelenting brutality, wrong and illegal from its first inception, now in its fifth year with no real exit in sight no matter who is elected this fall.

We have a systematic global program of kidnapping, assassination, secret prisons, torture, indefinite detention without charges or trial – all proclaimed as America’s right, institutionalized over the course of the past seven years and facing no more than tweaks and modifications through the normal processes of politics and government.

And we have a vast program of roundups, detentions, and deportations within this country – the burgeoning campaign against undocumented workers, with no resolution or end in sight.

And that’s only the beginning…

Another aspect of 1964: We didn’t know how it would all turn out. This whole movement has been so enshrined and mummified in the telling of history. Retrospectively it has been given the air of inevitability.

It was not inevitable. There was no road already there. “The road was made by walking” – and fighting.

The course of things was not at all clear then. Strongly-felt debates and struggles shaped strategy and tactics and philosophy raged at each stage of the struggle. These experiences opened many of us to new revolutionary ideas — which were being raised throughout the world at that time.

Where Is Our Mississippi Today?

* * * * * * * * * *

[timeline]

***W.E. A.L.L. B.E. Radio***A Philadelphia Story: Remembering Goodman, Chaney & Schwerner...

A Conversation With Ben Chaney (The Brother Of James Chaney) & Veterans Of Freedom Summer 1964

A Conversation With Ben Chaney (The Brother Of James Chaney) & Veterans Of Freedom Summer 1964

Listen To The Show:

http://www.blogtalkradio.com/weallbe/2009/12/17/Tha-Artivist-PresentsWE-ALL-BE-News-Radio

More Civil Rights Movement On W.E. A.L.L. B.E. :

http://www.blogtalkradio.com/weallbe/2009/12/17/Tha-Artivist-PresentsWE-ALL-BE-News-Radio

More Civil Rights Movement On W.E. A.L.L. B.E. :

No comments:

Post a Comment