Mukoma Wa NgugiAfrican In America Or

African American?

The riddle of identity means I can live in the US for 20 years yet still be treated differently – by both black people and white

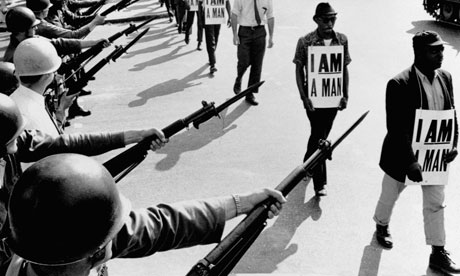

Africans who live in America do not share the history of struggle for civil rights, and indeed, even today, do not experience racism in the same way – the 'African foreigner privilege', Mukoma W Ngugi calls it. Photograph: Corbis

"You do not know what it means to be black in this country," an American-born son told his African father. He was right. White America differentiates between Africans and African Americans, and Africans in the United States have generally accepted this differentiation. This differentiation, in turn, creates a divide between Africans and African Americans, with Africans acting as a buffer between black and white America.

It is with relief that some whites meet an African. And it is with equal relief that some Africans shake the hand proffered in a patronising friendship. Kofi Annan, the Ghanaian former UN secretary general, while a student in the United States, visited the South at the height of the civil rights movement. He was in need of a haircut, but this being the Jim Crow era, a white barber told him "I do not cut nigger hair." To which Kofi Annan promptly replied "I am not a nigger, I am an African." The anecdote, as narrated in Stanley Meisler's Kofi Annan: A Man of Peace in a World of War, ends with him getting his hair cut.

There are several interesting questions here. Why would Kofi Annan accept a haircut from a racist? Why did he not stand in solidarity with African Americans who, at that time, were facing lynching, imprisonment and other forms of violence simply for agitating for their rights? And equally intriguing, on what basis did the racist barber differentiate between African black skin and African American black skin? Is an African not racially black? At a time of racial polarisation in the US, what made the haircut possible?

Being black and African, these are the types of questions with which I constantly wrestle as I navigate through myriads of confusing, illogical, but always hurtful and destructive racial mores. I was born in Evanston, Illinois to Kenyan parents. We returned to Kenya when I was a few months old. I grew up in a small rural town outside of Nairobi, and attended primary and secondary school in Kenya before returning to the United States in 1990 for college. I have now lived in the United States half my life. What I have come learn is that in the United States, being African can get you into places being black and African American will not.

For instance, take the "African foreigner privilege". In Ohio, thirsting for a beer I walk into the closest bar. Silence. I order a beer and the white guy next to me says, "Where are you from? Where is your accent from?" I say, "Kenya." Relief, followed by the words "Welcome to America. I thought you were one of them." The thirsty writer in me is intrigued. Now that I am on the inside, I can ask "What do you mean?" "Well, you know how they are," followed by a litany of stereotypes. Eventually, I say my piece but the guy looks at me with pity: "You will see what I mean." Never mind that to his "Welcome to America," I said I had been in the US for 20 years.

The end result of the African foreigner privilege, usually dispensed with condescension, is that Africans are becoming buffers between white and black America. There is now a plethora of reports comparing African students to African American students. The conclusion is that if Africans fresh off the boat are doing better than African Americans who have been here for centuries, then racism can no longer be blamed. But the reports do not consider that, just maybe, at either Harvard or a community college, Africans experience race differently from African Americans. Africans experience a patronising but helpful racism, as opposed to the hostile, threatened and defensive kind that African Americans grow up with. Racism wears a smile when meeting an African; it glares with hostility when meeting an African American.

Africans in the US can end up becoming foils to continuing African American struggles, because they buy into the stereotypes. They end up seeing African Americans through a racist lens. This is not to say that African Americans have not themselves bought into racist stereotypes of Africans, where Africans are straight out of a Tarzan movie. But to the credit of African Americans, they have actively, through organisations like Africa Action and Trans-Africa Forum, agitated on Africa's behalf.

Indeed, Nelson Mandela once said that without African American support, ending apartheid would have taken much longer. But one will not find organisations in African countries that reciprocate – for example, seeking to end a racialised judicial system in the US that sees more black men in prison than in college. And Africans in the United States tend to stay away from protests against police brutality and racial profiling. True, the fear of immigration police and offending the host country play a part, but I think there are ways in which Africans do not see the African American struggle against racism as their fight, too.

Twenty years and counting in the US, I no longer feel a conflicted identity, one is that torn between being black in the United States and African. Going to Kenya this past December for the Kwani Literary Festival, I saw no contradiction between going home to Kenya and returning home to the US. I do not fully comprehend terms like cosmopolitan. I do not float around in a universal home. But it makes sense to me that one can have two homes at the same time. Not just in the physical sense, but in the deepest sense of the word – to be rooted, and to have roots growing, in two different places.

And as a writer and citizen, I have duties to each. I want to open up the contradictions that, in Kenya, keep the majority in oppressive ethnicised poverty and violence and, in the United States, racialised violence and poverty.

As an African and a black person, I feel, rightly or wrongly, that I have a duty to love both homes. And love need not always be pleasant – it can be demanding, defensive, angry and wrong, but it always wants to build, not destroy.

via guardian.co.uk

No comments:

Post a Comment